Δ Light Readings : 016 - You cannot tell how soon it may be too late

Taking pictures in a place heavy with photographic history

Hi all, welcome back. One thing I’ve learned about creating things and putting them out into the world is that it increases your empathy and appreciation for other people doing the same. You admire their work more because you’ve done it, too, and you understand everything that happens “backstage” to bring it into being.

My name’s Stephen Voss and I’m a photographer based in Washington, DC. You can see my work on my website, and IG.

My next newsletter will be about my new book. I can’t wait to share with you.

If you dip into a photographic publication from the 1850s, what you get more than anything is chemistry. Take this passage from an article simply titled “Photography.” by Robert Hunt, published in The Photographic Art Journal, Volume 4, 1852:

Apply to the paper a solution of nitrate of silver, containing 100 grains of that salt to 1 ounce of distilled water. When nearly, but not quite dry, dip into a solution of iodide of potassium, of the strength of 25 grains of the salt to 1 ounce of distilled ed water, drain it, wash it, and then allow it to dry. Now brush it over with aceto-nitrate of silver, made by dissolving 50 grains of nitrate of silver in one ounce of distilled water, to which is added one-sixth its volume of strong acetic acid. Dry it with bibulous paper, and it is now ready for receiving the image.

The period at the end of the title seems to be a consistent stylistic choice throughout the journal, but it has the unintentionally hilarious effect of making it sound like the definitive, drop-the-mic take on the matter. I’m just picturing Hunt, quill pen in hand, finishing this piece, cracking his knuckles while letting out a self-satisfied sigh and thinking to himself, “Well, that settles it for all eternity.”

All of this to say that photography once attracted a different sort of person than it does today—someone willing to get their hands dirty, expose themselves to mercury and cyanide, and shave years off their life in the process. Someone like Mathew Brady.

The biographical history of the “Father of Photojournalism” can be found elsewhere. You may know that he pioneered the photography of war and went on to take portraits of just about every famous American of the day. One thing I learned recently is that he took few of the photos he is credited for. Due to deteriorating eyesight from the beginning of his photo career (looking at you deadly photo chemicals), he had a cadre of talented assistants actually making the pictures.

A few years ago, his grave site in DC was revamped with a slightly unhinged memorial. I was in the area for a shoot and stopped by to take a look. It features bronze statues of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, plus a raven perched atop a skull. It has a real “designed by committee” vibe to it.1

I mention this as groundwork for my interest in a particular room in a greige-colored office building, on a quiet part of Pennsylvania Avenue, about six blocks from the Capitol. According to Google Street View, the first-floor shades have been drawn since at least 2007.

On March 6, 2019, while setting up for a shoot in a neighboring building a few stories above, I looked down and noticed its unusual top floor. A series of seven double windows faced north, slanting inward at about a 20-degree angle.

This was the location of Brady’s studio during his heyday from 1858-1881. In this space, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses Grant and Frederick Douglass were photographed, in addition to countless other members of the wealthy class of DC. The slanted window was designed to let in the soft, steady morning light with most of the portraits sessions taking place between 8am and noon. Brady’s advertisements for his studio carried the tagline, “You cannot tell how soon it may be too late.” Nothing like a little existential dread to get people in front of the camera.

Describing the ways the world has changed in the one hundred eighty-something years since Abraham Lincoln sat there is a fool’s errand. Time lumbers forward, but the light still filters through these windows in the same way now as it did then. And I wanted to make a picture in that light.

Soon after my shoot, I’d reached out to the organization that owned the building. Initial plans were made, but then COVID put the idea on hold.2 In January of this year, I tried again—sending emails and calls and even dropping off a letter at the building’s front desk with security. I think they were a little exhausted by my persistence, and emailed me back to set a date.

On an unseasonably warm February morning, I met up with my friend Jared, and we headed inside. The building is an anomaly - a privately owned office building standing amongst enormous government buildings. Once inside, we were led to the 4th floor, down a hallway and into a room with a brass plaque on it that read, “Mathew Brady Room.” Bookshelves lined the walls—white from floor to ceiling. A massive table dominated the space. The slanted windows line the back wall, facing north.

Outside was cloudless and the sun reflected off of the window of an office building, drawing hard light across the room. The original design of the north-facing windows avoided this kind of direct sunlight, and I’m sure there was no tall building causing this glare back in Brady’s day.

I had it in my head that I should attempt a portrait using a long exposure time, similar to what Brady worked with due to the low sensitivity of wet plates. Using an ND filter, I set a thirty second exposure as Jared sat for me. Thirty seconds in a quiet room can stretch your conception of time. Thirty seconds of stillness and of controlled breath. It’s enough time for your mind to wander, to notice the faint hum from a heating vent, or the dust playing in the light that shimmered off a high window in the building across the alley. A soft click-close of the shutter ends this reverie as the exposure ends.

The floor of the building had been remodeled many times since Brady’s studio shut down in the 1880s as he faced financial problems and increased competition. There’s no way to know exactly where Lincoln sat for his portrait, or Frederick Douglass or Sojourner Truth (who knew quite a bit about the power of photography). Each of these people entered the building from Pennsylvania Avenue and walked up three flights of stairs to the studio where they would be photographed. Just three blocks away, Ford’s Theatre sits heavy with its own history.3

I get the sense that this room isn’t used often - that it mostly sits empty from day to day. That the intentional light let in by the slant of the window passes unnoticed. I left that room feeling a quiet respect for all the people—historical or long-forgotten—who once sat here, doing their best to hold still. For some, this experience might result in the only photograph ever taken of them in their lifetimes. For those thirty seconds, in a brief moment of a single day in their life, they surrendered themselves to the medium. Here they remain, letting their likeness be caught in time, recorded forever in the gentle wash of this immutable northern light.

An enormous thank you to Jonathan Townes at NCNW for letting me visit and photograph in the organization’s beautiful building.

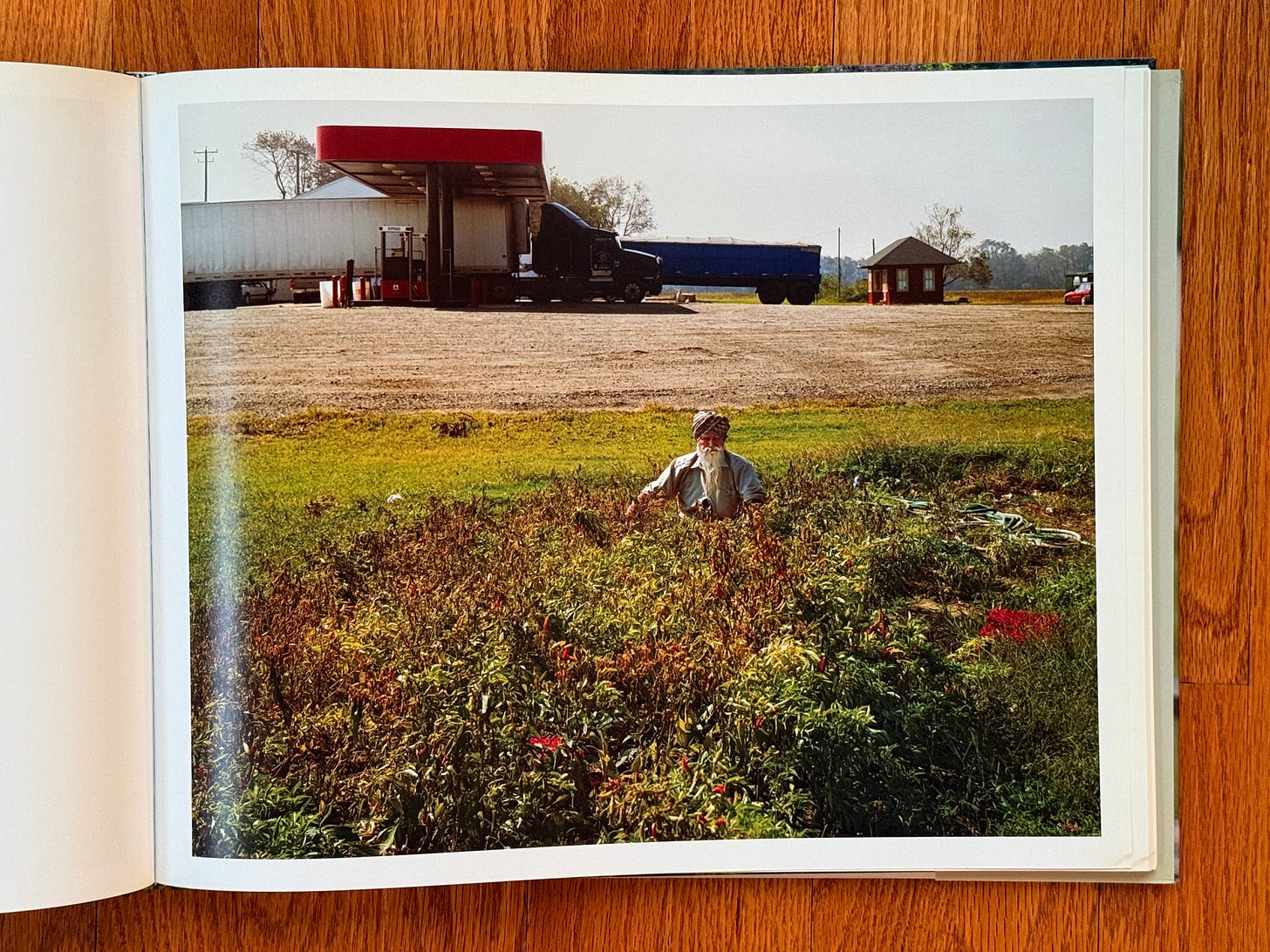

Page & Light

(a single page from a photo book I’ve recently looked through)

Currently

🛹🏙️You don’t have to be into skateboarding to appreciate This Old Ledge—a history of cities and urban planning told through the lens of skateboarding spots. Ted Barrow is a wonderful historian and art critic who also happens to be the best kind of tour guide, bringing his curiosity and expertise to these locations. This episode on Los Angeles’ Department of Water and Power is a great place to start.

❤️🔥🎶Fenne Lily - Lights Light Up - One of those songs you stumble across and can’t get out of your head. The Song Exploder about the origins of the song is quite nice. If that one’s too much of a downer, I’d check out the absolute ear worm that is One Way Train by Sunny War.

📕🚗In a few days, I’ll be driving up to New Jersey to pick up my new photography book from the printer and I’ll be sharing that all here first.

If you’ve made it this far and enjoyed the newsletter, I would greatly appreciate you sharing it by using the link below or posting someplace social. Thank you.

Lining the marble memorial are photos etched in granite of the individuals who played key roles in organizing and fundraising for this project, each accompanied by a brief inscription. Interestingly, a quick Google search shows that some of them are still very much alive.

Light Readings #2, dated March 9, 2020 optimistically mentions that I’ll be writing about this for the next issue.

Brady rarely photographed a scene without people in it, but he did make a picture of the chair that Lincoln was sitting in when he was shot at Ford’s Theatre.