I’ve tried to keep a firewall between my professional work and this newsletter, but it’s been hard to look away from the world these past few weeks. I spent Election Day into election night into the early morning hours in a parking lot in Wilmington, Delaware, awaiting what would happen next. The following day in Philadelphia, I saw demonstrators outside the building where ballots were being counted and a hastily-organized press conference in the parking lot of a private aviation company.

On Saturday, Washington, DC erupted as news organizations declared a winner in the presidential race just before lunchtime. The music of the city was car horns, jubilant and cathartic. Around the White House, a street party spontaneously came together on Black Lives Matter Plaza with go-go music and fireworks that only quieted down when the President-elect and Vice President-elect spoke.

In that moment, with crowds gathering around people holding up their phones to watch the speeches, I heard a different tone from those who will soon run the country. I mourned the brain space I’ve given over to these hostile and divisive times.

As always, I’m Stephen Voss, a photographer in Washington, DC. If you enjoy this newsletter, I’d appreciate you letting someone you like know about it.

Early in the pandemic, I came across the bronze bust of Sojourner Truth in the US Capitol Visitor’s Center. The bust had been unveiled in 2009 and the ceremony was attended by hundreds of people despite fears about a recent outbreak of swine flu.

When I walked through, the vast, marbled entrance lobby was empty. The shuttered gift shop still had a large Cherry Blossom Festival display up front, though the festival would soon be canceled and the trees cordoned off with police tape to prevent crowds from gathering.

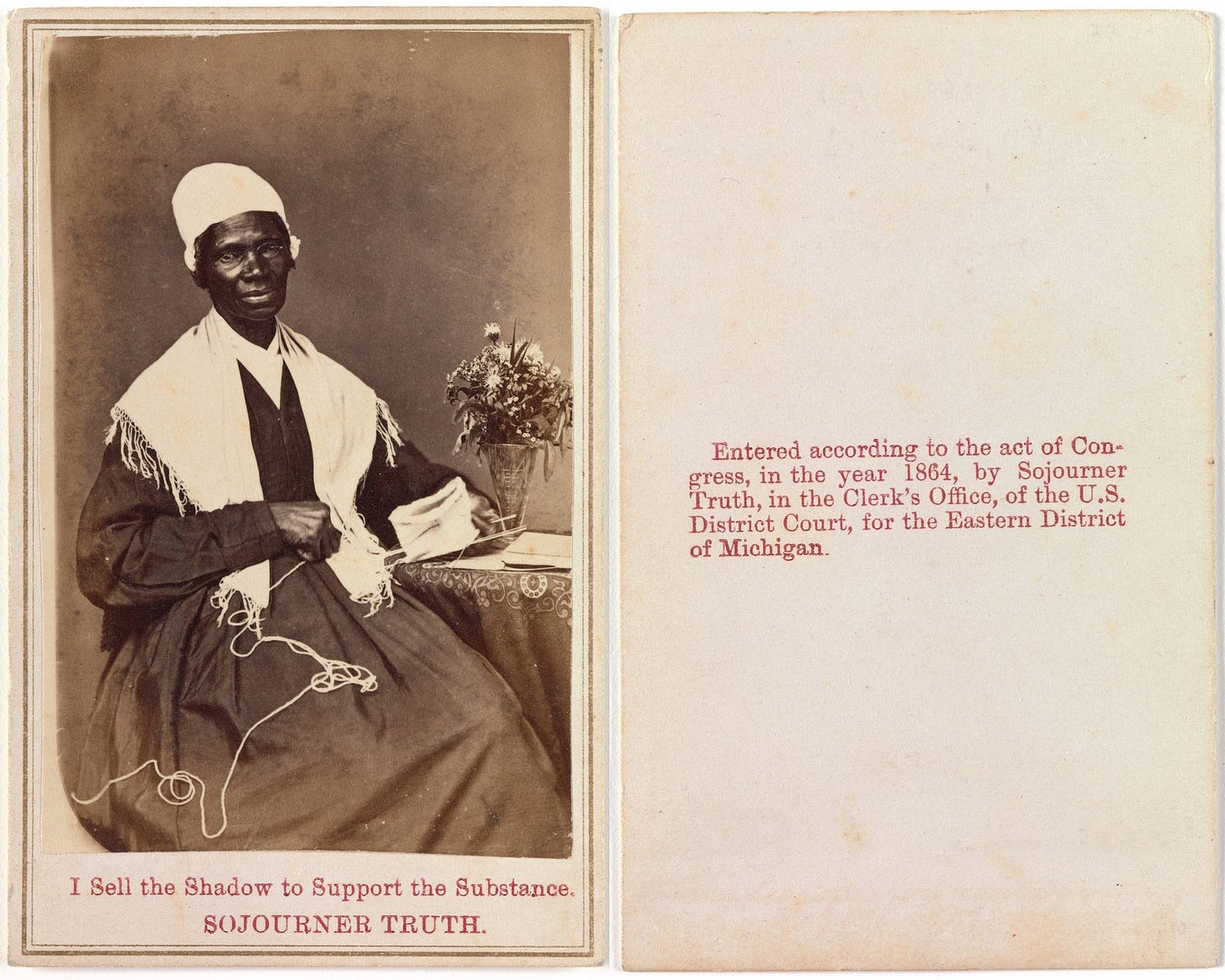

The bust stood on a speckled, black marble base, behind a pile of stanchions herded in a corner. I knew Sojourner Truth as a former slave and abolitionist, a woman whose first language was Dutch. But in digging deeper, I found someone who had quickly and definitively divined the power of sharing one’s likeness in a photo. Photography had only recently become affordable to the general public through the creation of cartes de visites, a 2” x 3.5” sized portrait process that could be made inexpensively. It quickly became a sensation through Europe and the United States. Truth seized upon these modest printed photos that would sustain her activism for the rest of her life.

At speeches and through the mail, Truth sold cartes de visites that featured a photograph of her that she had commissioned and the phrase:

I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance.

The “shadow” she refers to is the photo itself. In the early days of photography, making a photo was thought of as catching a shadow and photographers were sometimes colloquially called “shadow catchers.”

And to be clear, she did not stumble into this source of income as a lucky accident. Truth understood that her outward appearance could be used to advance her cause. Photography’s short history at that time often was often a story of oppression and power (not so different from today) but Truth turned it into an assertion of strength and activism. At a human rights convention, she said that she “used to be sold for other people’s benefit, but now she sold herself for her own.”

In a move that will resonate with photographers today, she even went so far as to copyright her name to prevent others from profiting off of her.

As a brief aside, I LOLed at this line in a letter written in the Anti-Slavery Standard announcing the new photos, “…it will be, likely, two or three weeks before I can get the photographs, the artists are so slow.”

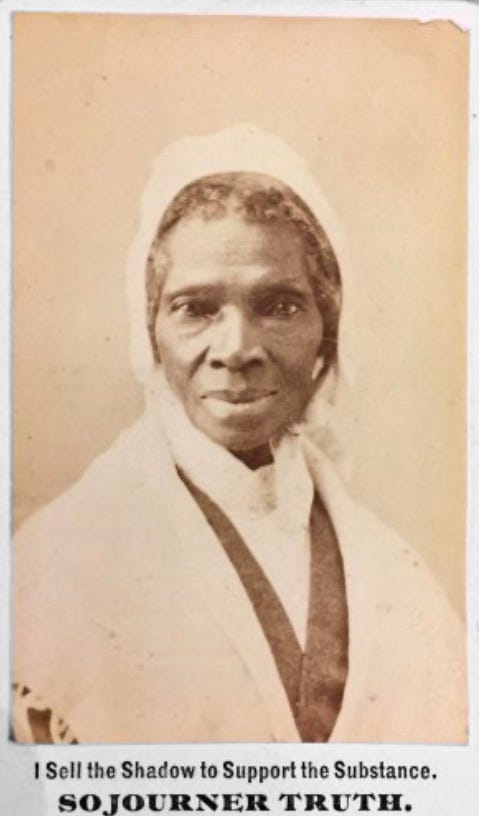

Truth continued to have portraits made throughout her life. But this one, taken just a year before her death, is unlike any of the previous photos. In it, Truth has taken her glasses off and her bonnet is pulled back a bit to reveal her hair. Natural light comes in from the left of the frame, allowing for just a glint of a catchlight in her other eye.

The limits of the medium make her bonnet’s fabric go pure white, framing her face in a pale sepia glow. Her shawl is neatly arranged and the lines of the dark undercoat lead you up to her face bearing that inimitable expression. Truth’s hard, uncompromising gaze has softened, her mouth almost hinting at a smile and her eyes hold steady as she stares at us through time. We no longer just see the fierce abolitionist, the truth teller, but instead a woman who has lived a life, who was illiterate her entire life yet wrote a biography, who suffered myriad health problems but continued to travel, write and sell those cards into her eighth decade of life. To her end, Truth knew that her image, her shadow, would outlast her, that the way she had chosen to be seen would be how we might all see her throughout time.

The contemplation of things as they are

without error or confusion

without substitution or imposture

is in itself a nobler thing

than a whole harvest of invention.

-Francis Bacon (a quote photographer Dorothea Lange had pinned outside her darkroom)

Three Questions with Andrew Jackson

Andrew is a photographer based in Montreal, Canada. His incisive and thoughtful work had stuck with me since the moment I first encountered it. I can’t recommend his book, From a Small Island, enough. There are only a few copies left and you can order it here.

What’s one non-photography book that you think every photographer should read?

I’m very interested in notions of representation and who, within photography, gets to narrate the story.

So the non-photography book which I would recommend to your readers is Between The World And Me by Ta-Neshi Coates. It’s a book where Coates explores notions of his subjectivity and selfhood as a Black American. It is also about how history has impacted upon and continues to shape his notions of selfhood. And also how these are shaping his son’s selfhood.

These words would have been less powerful if they had been filtered through the writing of someone who had not directly lived Coates's experience. I’m not saying that only people from specific communities can ‘report’ on these communities, but that perhaps all photographers should ask themselves if they’re really the best person to tell the story they are about to undertake?

If we consider that, within the academies where photography is being taught to new generations of photographers as being a research-based and driven practice, if this is the case, shouldn’t the person with the greatest understanding of the subject be the one to represent it?

For a moment, over the summer, when many famed institutions within photography proudly posted their Black tiles to Instagram, there seemed to be a willingness to increase the range of voices in photography. Sadly, that has proven only to be an act of virtue signalling by so many.

Is there something you tell yourself or remind yourself of before you go out to make pictures?

I’m focussed on producing works which explore my own lived experiences, ones explicitly shaped by transnational migration and the ensuing notions of home and belonging which they engender.

My parents migrated from Jamaica to England, where I was born, and I’m now living in Canada. I’m interested in how shifting geographical space affects one's psychological space. Most recently, until I had to stop traveling to Jamaica and Britain, I have been developing the second and third chapters of a trilogy of works, after the first chapter, From a Small Island, to continue to explore the inter-generational experience of migration from the Caribbean to Britain.

Working on these long-term, self-initiated works come with a sense of insecurity, which perhaps, while I’m researching and producing them at least, requires an expenditure of both time and money, invariably which, until the work has found an outlet, won’t get financially recouped.

I often get through this by telling myself that by recording these stories, and creating platforms which share these experiences, I’m contributing to a range of approaches which show that these migrants from the Caribbean and their descendents were there in Britain. We cannot ignore them; their lives matter - especially so in a post-Brexit landscape which perhaps is questioning who does and doesn’t ‘belong’ more than ever.

Perhaps I sustain myself by thinking what I’m doing is of purpose and value. Even if I didn’t make a penny from the work now, if, in ten or twenty years time, there is only one young person who can find themselves reflected in the work and gain an understanding of how it connects to the past, and to a history not readily discussed in Britain, that will be enough.

Has there been any piece of art (music, books, paintings, photos, etc.) that has felt sustaining to you during these times?

I can’t deny that it hasn’t been a tough time. The pandemic has erased so much of what I had hoped to do this year, as it has for so many, and yet it has brought so many unexpected possibilities too. I used to travel a lot, particularly back to England to see family and for work, and the inability to do that, with an ageing father, has been very difficult.

Initially, in that first undulating period it felt like wow, this is like a surreal holiday where I can eat and drink whatever I want - whenever I want! At that time, Netflix and other online streaming sites became sustaining.

Coincidentally, I had been working on a written commission with the Living Memory Project in the UK and Sandwell Archives, where I was writing a story about one day during the Second World War as experienced in a town called Smethwick (my home for many years) using the artefacts in the archive as a foundation to this work. The story took place during the Blitz, which, in a nine-month period of bombing, killed 40,000 people across Britain.

The parallels between how people discussed the surreal nature of the early days of the Blitz - and how easily they had slipped into ‘new normals’ as they accepted their new lives within it - seemed so relevant to what I was experiencing in the first days of lockdown.

I found myself drawn to read more about how people overcame and came through the war, perhaps in some strange way finding answers of how I too could come through the pandemic? Not that I’m equating this current time to the horrors of the Second World War - because I’m not - but I found the pathways others had found through their own ontologically uncertain times strangely compelling.

If anyone would like to read my story, you can find it here : In The Night of the Day

Currently

I related to a lot in Oliver Burkeman's last column: the eight secrets to a (fairly) fulfilled life, especially:

It’s shocking to realise how readily we set aside even our greatest ambitions in life, merely to avoid easily tolerable levels of unpleasantness. You already know it won’t kill you to endure the mild agitation of getting back to work on an important creative project; initiating a difficult conversation with a colleague; asking someone out; or checking your bank balance – but you can waste years in avoidance nonetheless. (This is how social media platforms flourish: by providing an instantly available, compelling place to go at the first hint of unease.)

❄️🚲A brilliant play-by-play by Sam Anderson of the magical Lyon snowball fight from 1897.

🎹 😴“No, no, this is not piano, this is dreaming.” A much-needed 59 seconds of bliss from an old interview with Duke Ellington.

Stay safe and thank you for your time. I hope you’re well and making it through. If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, I’d appreciate you sharing it.