Greetings kind Light Reading followers, happy to have you here. If you signed up for this and don’t know who I am, my name’s Stephen Voss and I’m a photographer living in Washington, DC. I photograph politicians for magazines, and, occasionally, bonsai trees. You can see my work on my website, and Instagram.

Have you fallen into a routine yet? Have you awoken to a new morning, begun your day, then inexplicably it’s 3pm with little sense of what happened in between? Have you made bread, then stopped making bread? Are you longing to sit down at a favorite restaurant and have a menu put down before you? Just to sit there, savoring the choice, and knowing that whatever you order will be personally cooked and walked over to the table you’re sitting, then put down right there in front of you, without an ounce of effort on your part?

Onto the newsletter, I’m trying something new - an interview, albeit a short one rather than the full-length one from last issue. One photographer, three questions, starting with an absolute favorite of mine, Simon Norfolk who also shares some work he has been making during the COVID-19 outbreak.

As always, I appreciate you sharing this newsletter with others.

Sam Abell came out with a book called Seeing Gardens in October, 2000. The book has always been one of those sleeper hits that photographers often cite as a favorite.

The writing that accompanies the images in the book is deeply site specific, like the piece that accompanies this photo, after Abell had lost most of his camera equipment in an overturned canoe:

The open tundra was consoling. Most of the low plants were new to me, but some I recognized from home. Here, though, they were miniaturized by the severe growing conditions.

I was thinking about this when an owl and I surprised each other. It flew up abruptly but then didn’t fly off. Instead, it silently circled my head several times at close range. I didn’t move until the owl flew away to the horizon.

When I returned, my camera was raised. I pressed the shutter as the owl rose over my head, taking on the shape, for a moment, of the bird that sits atop a totem pole.

So, it was interesting to read what he (or, honestly, whoever copy writes his web site) had to say about the book in the description accompanying it on SamAbell.com—

It is a stealthy photography book. Nominally this appears to be a book of garden photographs, but Abell uses gardens and the 'seeing' of them to subtly discuss the fundamentals of photography, from framing and lighting, to scale, and to the persistent importance of moments even in apparently still situations.

Abell rarely gets at this level of abstraction in the book and I wonder if he always meant for the book to be read this way or if this clarity came later.

But, this is a feature of the great photo books, no? They’re not often about the subjects of the photos. In the fine art photography world, this almost goes without saying— your photographs can be seen to be as much a comment on the nature of photography itself as they are images of a thing.

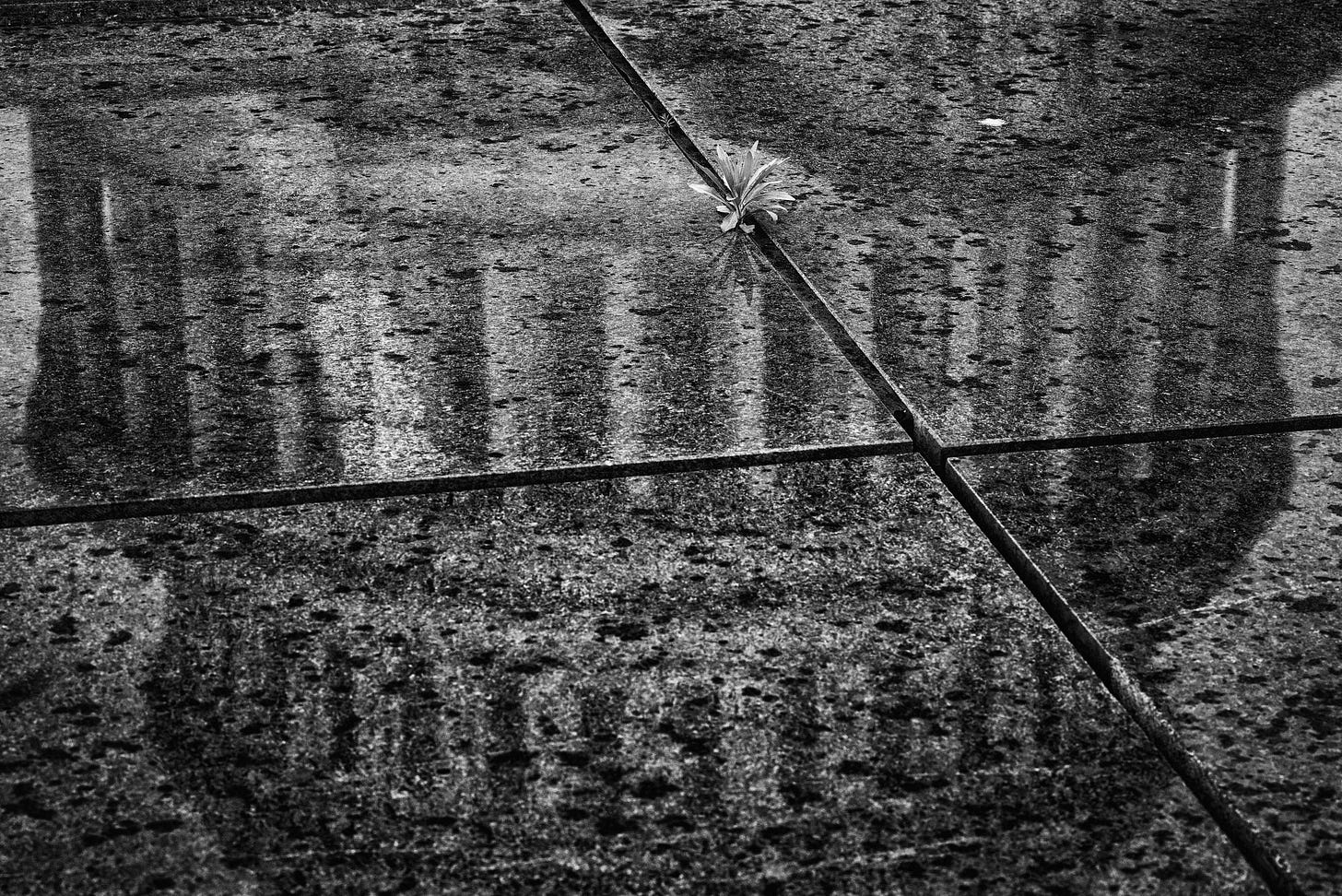

Rose Mallow, Chelsea Physic Garden, London

But, for an old school National Geographic photographer like Sam Abell (albeit one who always seemed a little out of step with his more bombastic NatGeo peers), this gets at the real value of the book. Abell’s photos can sometimes feel like a puzzle within a puzzle. They can seem like a hard-won education to be had if you spend the time. He tends to actively resist any notion of “decisive moments” in this book, offering these photos as a minimalist response—a Zen koan really—to the hypothetical question of what a photograph can be.

Abell inhabits an unsettled and ill-defined area between fine art and documentary photography, though he’s clearly tilting the scale towards documentary. But his photos have intent, a theory of the case, in a way that many photojournalists might be uncomfortable owning up to.

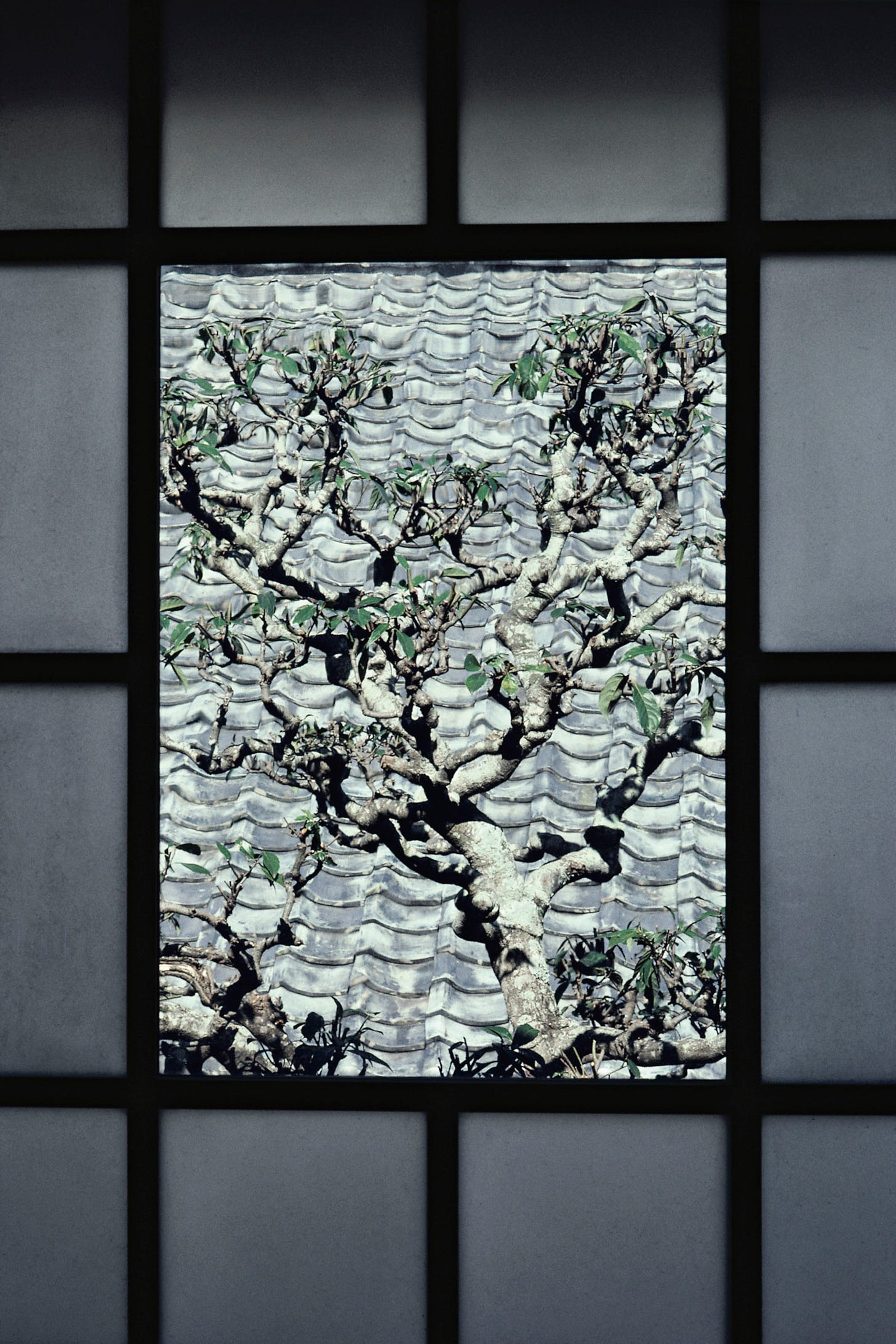

Tomoe Ryokan, Hagi, Japan

I think we can understand a lot about photographers by trying to figure out what questions they’re trying to ask in their work. And I doubt Abell spends much time thinking about objectivity and truth. I don’t mean this at all as a knock on his photojournalistic creds, but looking at his photos convince me he’s concerned with other things in his work. Their formalist quality reveals his strong bent towards structure and the symbolic and literal meaning of the subjects contained therein.

All that said, I find some of the photos in this book underwhelming. I sometimes wonder what the heck Abell was seeing when he raised his camera to a scene. But there’s enough magic in these pages that I’m less inclined to dismiss the work I don’t like. It’s made me curious to lean in a bit and to give him the benefit of the doubt.

Sometimes it’s worth considering a picture in the context of a certain sequence in the book. Or maybe, maybe, what I don’t like about a photo is in fact a potential lesson to be learned. Could it be a suggestion of an alternative path my own work might take that I’d previously dismissed for long-forgotten reasons?

Or maybe, there are just some underwhelming photos in here [shrug emoji]. But I like the idea of using someone else’s work to question some of my base assumptions about my own photo making. And, even when I do ultimately decide one of Abell’s photos is not for me, the path to get there is in and of itself, rewarding.

—

Three Questions with Simon Norfolk

I’ve followed Simon Norfolk’s work for years (while shaking my head sometimes at the sheer insanity of bringing large format cameras to war zones). What I’ve always appreciated most about Norfolk is his keen reading of human history. His photos are made with an understanding of what’s come before and, especially in the case of his current work mentioned below, a somewhat prophetic vision of what comes next.

What’s one non-photography book that you think every photographer should read?

The non-photography book I would give to photographers would be Mountains of the Mind: A History of a Fascination by Robert MacFarlane. It shows why the English, in particular, in the 18th century took to the mountains to find the find their souls; it explains the Romantic dreaming of wilderness and altitude and emptiness and the Sublime (which I’ve tried to place in all my work for 20 years). And it ends explaining why in 1924 the English mountaineers Sandy Irving and George Mallory climbed to what they new would be their deaths on Everest. The letters between Mallory and his wife Ruth are heartbreaking. It’s the book that justifies for me why I am pre-fabricated, in every sense of the word, for the outside.

At the moment I’m reading a lot of books about the paleolithic cave art, my new fascination. I went to Lascaux last year and my head is still fizzing with the thought of it.

Is there something you tell yourself or remind yourself of before every photo shoot?

Yes, it will be worth getting out of bed at 4am for. And it always is, even if just for the birdsong.

Has there been any piece of art (music, books, paintings, photos, etc.) that has felt sustaining to you during these times?

I’ve been shooting in the City of London very early in the morning for most of the quarantine. I started because horrible, sweary neighbours moved into the house next door and I needed to get away and 4am seemed the safest time to go out.

Here’s what I wrote and my inspirations:

Lost Capital

In Gustave Doré’s 1873 engraving of The New Zealander, a lonely traveller, in centuries to come, sits by an overgrown River Thames. Across the water are the lifeless ruins of a future London, the crumbling dome of St. Paul’s as decayed as the Roman Colosseum is today. New Zealand was imagined by Doré as so remote that it would escape the West’s imminent collapse and our Kiwi ponders the ruins of an earlier, collapsed civilisation just as an English noble might have done on his “grand tour” in Rome.

One of the things I love about the Grand Romantics was they had the courage to imagine a new society but also the humility to see beyond that, to how the world would be when even their paradise had come and gone. The meme of The New Zealander has had a long life. There is a direct line from him to the dystopian cities of JG Ballard and Cormac McCarthy, to a thousand zombie movies. He’s behind all those computer games that feature the lonely avenger scouring the streets of a post-apocalyptic city.

Constantin-François Volney, who travelled in Egypt and Syria in 1784, wrote in his book Ruins, or a Survey of the Revolutions of Empires:

What are become of so many productions of the hand of man? Where are those ramparts of Nineveh, those walls of Babylon, those palaces of Persepolis? … Alas! I have beheld nothing but solitude and desertion! Who can assure me that the present desolation will not one day be the lot of our own country? Who knows but that hereafter some traveller like myself will sit down upon the banks of the Seine, the Thames, or the Zuyder Zee, solitary amid silent ruins, and weep a people [extinct], and their greatness changed into an empty name?

The Romantics thought our society would collapse from the emptiness of its values or the inequalities in our economies. Even the imaginations of Shelley or Byron couldn’t factor in a virus from a pangolin in the wet market of a provincial Chinese city.

In photographing Coronavirus London, I was astonished that by removing from the streets the daily dross of life (cars, trucks, people) suddenly the architecture shone forth. Buildings look like the architect's plans of them; unblotted, sharp. I’m reminded of the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, their linear clarity and brilliantly lit dreamscapes. I never noticed how London is a grand Imperial chessboard with all the architectural pieces laid out awaiting the cavalcade. I thought of city as ‘Lost’ because a) this London was lost beneath the cacophony, b) I often got lost down side-streets I thought I knew intimately and c) we’re all a little lost, at sixes and sevens right now.

I felt much like I did when I was in a bombed Afghanistan at the beginning of my career searching a shattered battlefield absent of soldiers; a stage without actors and me, the New Zealander, scratching for clues.

Empty London is a Momento Mori or a Vanitas painting; it shows that this microscopic virus has made proud fools of us all. It has shown us to be ultimately powerless and our investments misguided and empty. All our dreams and schemes and the protections that insulate us from the world were found to be as tough as wet cardboard. Even the most comfortable of us is scrambling round the internet for toilet roll and PPE. Omnia vanitas.

The only people I meet on my dawn trips are the bronze statues of the grandees of the British Empire (‘Good morning, Your Grace’) who stand slightly-disappointed, looking down on the mess we’ve made of their inheritance. They resemble Easter Island’s Moai left guarding the sacred groves of a religion no-one follows. Everyone’s gone to the Rapture. London looks magnificent whilst looking as if it has been hit by a neutron bomb. I never imagined the Apocalypse would be so quiet one would hear in Piccadilly the song of a blackbird.

You can view Simon’s photographs as part of The COVID-19 Visual Project, as well as on his Instagram page.

Currently

🍗☕️Reading this incredible story of art critic Jerry Saltz’s life up until now. His *insane* diet is honestly a little hard for me to get my head around, but his journey to art critic (and writer of one of the great “how-to’s”) is a wild and pleasurable read.

💨🕶Remember that song, Wind of Change, by The Scorpions? What if it wasn’t actually written by the band, but instead written by the CIA? New Yorker investigative journalist Patrick Radden Keefe looks into it in this fun and fascinating podcast.

😷📸I had a strange few days at the US Capitol for a story and spent a lot of time walking through empty Senate building hallways.

Thanks and take care. If you liked reading about Sam Abell and what Simon Norfolk’s been up to recently, I’d appreciate you sharing this newsletter.