It’s a hard thing to admit, but at the beginning of my photography career, I was indifferent to its history. My early photographic education came from sitting at the cafe at Borders with a pile of magazines spilling over the table, absorbing megapixel counts and “Ten Tips to Improve Your Landscape Photography,” (hot tip: level horizons, good!). It took me years to kick this habit. Years to grudgingly read Edward Weston’s Daybooks or appreciate Eugene Atget’s photos of Paris that once felt irrelevant and impenetrable to me.

All of this is to say that when I came across Elliot Porter’s work for the first time, I did not rise to the occasion. If you don’t know of his work, a ruthlessly-edited summary would be: Ansel Adams, but in color.

I had lumped Porter’s work with that particular type of coffee table photo book that seemed ever-present in the American middle class living room of the 60s and 70s. Those hefty glossy-paged paperweights of a book featuring glowing scenes of bucolic nature. All made possible by Kodachrome 64 and improvements in the economy of book publishing.

I suspect that most of these books were received as gifts, flipped through once and set down, never be opened again. The photo sections of used book stores bear this out with entire shelves straining under the weight of American’s National Parks, and Earth From Above.

But, like so many artists doing something new, it was Porter’s imitators that created the boring, derivative work. His images were a quiet, understated revelation.

To appreciate an Eliot Porter photo is to appreciate the act of looking closely. He was not seeking the brass-band-marching-down-the-street drama of his contemporary Ansel Adams. His work was all subtlety and finesse.

Looking back, it’s amazing to see this practitioner of nature photography be handed a new kind of film, with the ability to record the colors he sees out in the world. And, instead of chasing down fiery sunsets and luminous Fall color, he pulls back hard on the reins and makes photos that are a study in restraint and context.

I can only imagine a present-day Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter sharing their images on Instagram. Adams would undoubtedly be raking in the likes and fire emojis while Porter’s images would mostly be overlooked, receiving no more than an occasional, “Nice.”

In Porter’s work, no effort is made to reach out and grab you. Instead he’s inviting you in, to come stay awhile.

If there’s an image that first drew me in, it’s this one, entitled Tamiami Trail, Florida. The image frames two pairs of large Cypress trees in a marshy wood, the thin forest stretching off to a pale horizon.

The photo has this great balance to it and most of it barely has any color at all. But, coming in from the right-center of the photo are these splashes of orange flowers that feel like they’re dancing across the scene. Some of them are little blurry, with the very long exposure it must’ve taken to get that front to back sharpness.

Porter trusted these flowers to hold the frame together, to add a needed bit of chaos. Moreseo, he trusted you, the viewer, looking at this photograph forty-six years and two months after he made it, to see and appreciate them. This connection is what has me diving into early photo history here—these early photographers were dealing with the same issues that we do. They were struggling to make a photo that would last, that would remain meaningful and that might reach out and grab you decades later.

This is the through line for me—a realization that despite the technological leaps, a lot of what photography is remains the same. Maybe the Old Masters didn’t figure it all out, but their efforts mirrored our own successes and failures and maybe there is something to be understood from those struggles.

Currently

Last Wednesday, I asked people on Instagram to send me images. I’d offer some thoughts on them and post it as an Instastory. The response has been overwhelming and time-consuming in the best way. I’ve been compiling all of the images and my comments into a highlighted Instagram story (or two).

Also, I’ve been photographing my family. I know that sounds pretty basic on the face of it, but it’s been years since I’ve seriously photographed our home life using something other than a cell phone. It took a real, live assignment to get this going and I’m deeply grateful for that. Can’t wait to share.

This NYT 52 Books for 52 Places list is such a great escape for these times. I’m currently reading Island Home by Tim Winton about the wildness of his Australian upbringing and his fight to preserve underlooked parts of that country.

Lastly, I’m enjoying Red and Green Yuzu Kosho, a spicy, citrusy condiment that Helen Rosner wrote about in her spectacularly-titled ode to yuzu. So far, it’s added a nice kick to some scrambled eggs and roasted carrots.

Thank you for giving me your time. If you have a moment, I’d love to hear what these past weeks have been like for you.

If you’re a photographer, have you picked up a camera?

Have you made any images that felt right to you in this moment?

If you’re willing, I’d love to share some of your photos and responses in an upcoming issue of Light Readings.

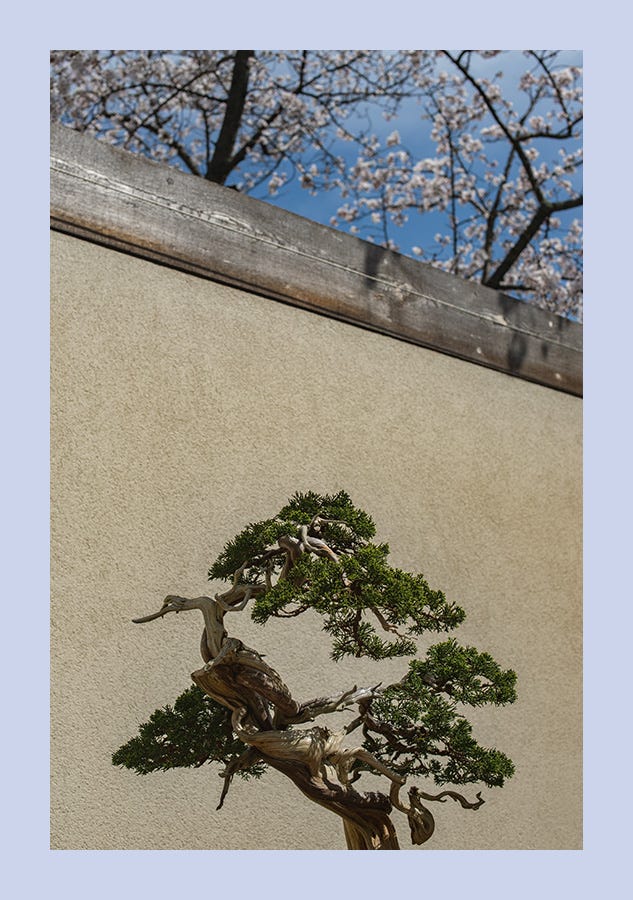

If you signed up for this and don’t know who I am, my name’s Stephen Voss and I’m a photographer living in Washington, DC. I photograph politicians for magazines, and, occasionally, bonsai trees. You can see my work on my website.

I started this newsletter because I missed creating things and sharing them with the world. I missed making new things that didn’t come from assignments.

If you’ve made it this far and enjoyed the newsletter, I would greatly appreciate you sharing it by using the link below or posting someplace social.

Thanks for reading and stay safe.

Photos

1. Closeup of image from Galen Rowell’s Mountain Light book

2. Tamiami Trail, Florida, by Eliot Porter

2. Our backyard

3. Bonsai and cherry blossom at the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum in Washington, DC