Δ Light Readings : 001 - Introductions are in order

by Stephen Voss

Welcome fine Light Readers to something new.

I’m Stephen Voss, a photographer living in Washington, DC, making a living taking portraits of people for magazines and newspapers.

I grew up on the internet, from running a BBS and participating in USENET groups, to publishing a blog in the early aughts. I remember when Joerg Colberg’s Conscientious was more or less a links blog and I spent hours reading about obscure film cameras I could never afford at the time.

I’ve been thinking about firsts given the “001” at the top of this email (those two preceding zeros are admittedly an act of some hubris).

In this spirit, I’m also reading introductions to photo books, from the classics like Kerouac’s beat-rhyme-poetry mood setter for The Americans to Patricia Hempl’s childhood fairytale of the flooded Mississippi in Soth’s modern classic Sleeping by the Mississippi.

The good ones have a sort of rhyme with the photos. They don’t try to do too much and they don’t (Kerouac notwithstanding) grab on too tight to any specific photo.

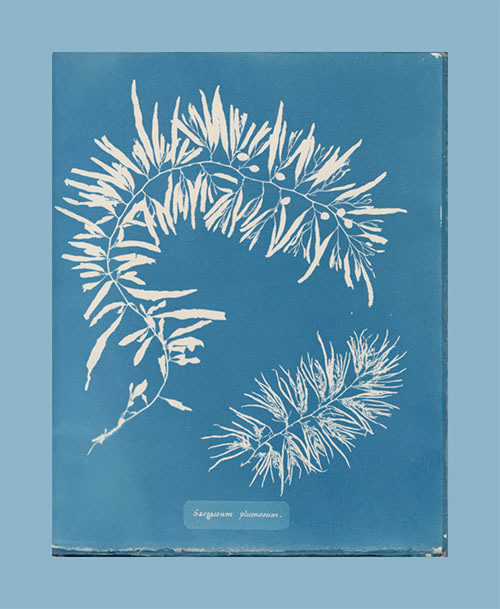

But before Kerouac and Hempl, there was photographer Anna Atkins, who published what is widely regarded as the first photo book ever, in October 1843, with the endearingly dry title of Photographs of British Algae.

In her introduction she writes:

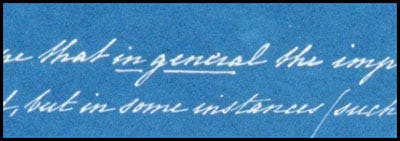

“I hope that in general the impressions will be found sharp and well-defined, but in some instances, such as the Fuci, the thickness of the specimens renders it impossible to press the glass used in taking photographs sufficiently close to them to ensure a perfect representation of every part. Being, however, unwilling to omit any species to which I had access, I have preferred giving such impressions as I could obtain of these thick objects to their entire omission. I take this opportunity of returning my thanks to the friends who have allowed me to use their collections of Algae on this occasion.”

As seen above from the original, the words “in general” are underlined, which I love. It feels like a dry rejoinder to any criticism she might receive on the quality of the image. For some context, her friend had just recently invented cyanotypes and she’s in the process of literally creating the first photo book ever, but still feels the need to qualify the work, to push back against the anticipated 19th century trolling.

But then she shows her determination in the next sentence, willing these seaweed prints into existence even if the quality didn’t meet her standards.

And it should be said, her prints are magical, glowing records of light. This first book is not just a document of British algae but an understanding of the potential of this new medium to create something beautiful and emotive that stands on its own merits.

Let me end this with the delightful visual that occurred to me when I read the last sentence of her introduction. Atkins, in her home village of Halstead in southeastern England, strolling through the rolling countryside to return bags of seaweed collected by her coastal neighbors. Each bit of seaweed having had its moment in the light, pressed flat under glass, immortalized underneath a sky colored the brand new blue of a cyanotype.

—

Thank you for reading this far. Another newsletter is already in the making that will include a few more diversions, links and gear reviews (kidding about that last one).

I’d be grateful, if you found this interesting, to share it with someone, or to simply respond here letting me know.

-Stephen

Photo credit at top: Anna Atkins, “Dictyota dichotoma, in the young state; and in fruit” used with permission from NYPL Digital Collection.

I had the pleasure of seeing this work at the NYPL a couple of years ago. It’s insanely inspiring and amazing how well the pages have held up. The prints feel alive viewed in a dimly lit room. The blue so subtle...